Goal Attainment Scaling is a goal-setting approach that is useful for both for documenting outcomes and for demonstrating those outcomes to insurance companies. How often do we know we’ve helped someone improve with therapy, only to do the re-assessment and find no change on the standardized measure? How long until insurance stops reimbursing in these situations?

After listening to an excellent ASHA course on cognitive therapy for TBI (free to ASHA members until 6/30/2020), I finally understand Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) well enough to try it out in my own practice. The information in this post primarily comes from Don MacLennan and Dr. McKay Moore Sohlberg’s course, as well as King’s College London’s resource page.

Free DIRECT download: GAS worksheet (patient handout). (Email subscribers get free access to all the resources in the Free Subscription Library.)

Outline:

- What is Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS)?

- What can we use GAS for?

- Examples of GAS goals.

- How do we write goals using GAS?

- Free tools for calculating the GAS score.

- Learn more about GAS.

- Try Goal Attainment Scaling with a patient.

- Related Eat, Speak, & Think posts.

What is Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS)?

GAS is a measurement tool that we can use to:

- Develop personalized goals that are meaningful and important to our patient.

- Collaborate to identify different possible outcomes.

- Develop a shared understanding of reasonable expectations from therapy.

- Measure how well a person achieved their expected outcomes.

Although it’s personalized to each patient, the results are statistically valid. In short, it’s a personalized goal setting tool that serves as its own outcome measure.

Here’s the format. For each level, we write a specific goal (ideally, written as a SMART goal):

- +2: Patient achieved a lot more than expected.

- +1: Patient achieved a little more than expected.

- 0: Patient met goal as expected.

- -1: Patient achieved a little less than expected. (Usually the baseline, see below)

- -2: Patient achieved a lot less than expected.

We work with our patient to determine a reasonable goal to achieve in the time we have and write that outcome down at level 0. We write their current level down as -1, unless it’s not possible to perform at a lower level. In that case, we set their current level down as -2. Then we fill in the missing levels. The difference between levels should be equal.

Before you check out the examples, take a look at what we can use GAS for. Then we’ll look into how to write goals using GAS.

What can we use GAS for?

SLPs can use GAS to develop goals in every area that we treat. GAS was first described in 1968 for measuring outcomes for mental health interventions. Since then, GAS has been used in many fields of medicine and is used by rehabilitation professions working with children and adults.

More specifically, here are some rehab areas that the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab lists:

- Activities of Daily Living

- Aphasia

- Balance

- Behavior

- Cognition

- Communication

- Depression

- Dysarthria

- Life Participation

- Pain

- Quality of Life

- Reading Comprehension

- Spasticity

- Incontinence.

We can also use GAS to develop goals for apraxia of speech, dysphagia, and voice as well, which I think covers the broad areas SLPs address.

Examples of GAS goals

As you look at these examples, notice that the difference between levels is (roughly) equal. In order for the outcome measure to be statistically valid, it’s important that the outcomes be divided into five levels with equal distance between each pair.

Self-grooming and sustained attention

Here’s a video showing a clinical advisor walking an occupational therapy student through setting goals for two different patients, one for self-grooming and the other for sustained attention. They’re very clear examples, and it’s interesting to hear how the clinical advisor adjusts the outcome levels.

Increasing study time

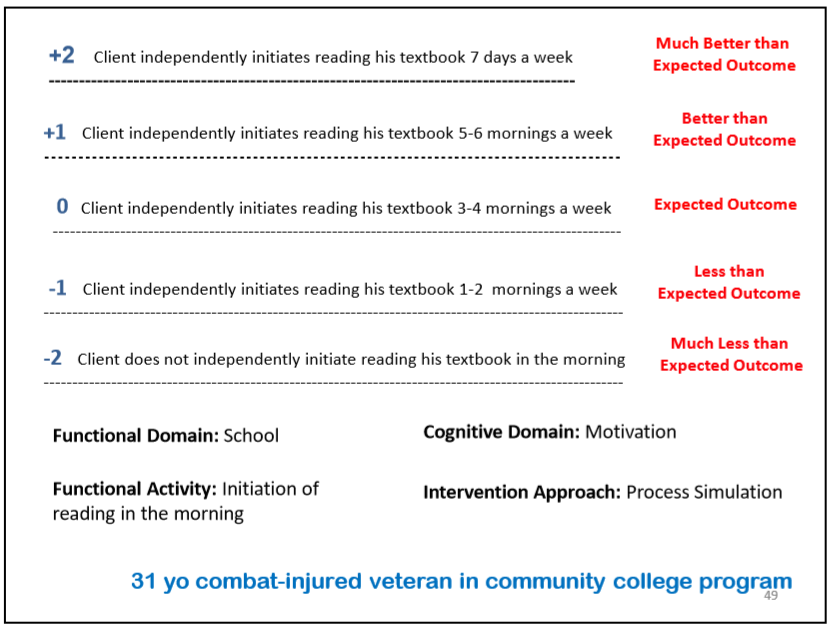

I’m including the following two slides from Don MacLennan and Dr. McKay Moore Sohlberg’s fantastic course Beyond Workbooks: Functional Cognitive Rehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injuries, with permission.

This example is for a 31-year-old college student who was trying to study propped up in bed before going to sleep. Needless to say, it wasn’t working well.

He was trying to study in the morning, but was only managing one or two mornings a week, which is set at outcome level -1. If this is where he ended up after therapy, it would be a “less than expected outcome.”

Working with his speech-language pathologist, he decided that a reasonable goal would be to read his textbook three to four mornings a week, which is set at outcome level 0.

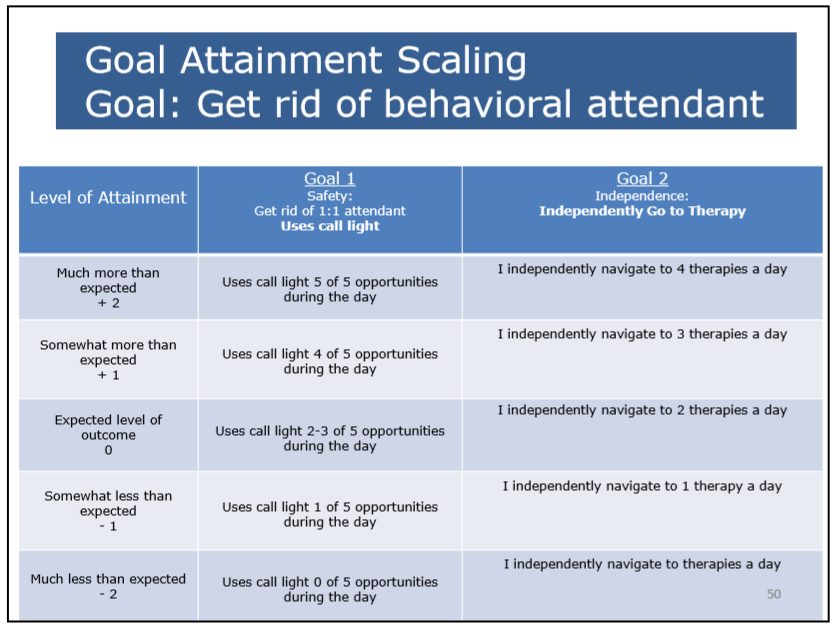

Using call bell and wayfinding

Here’s the second slide from MacLennon and Sohlberg’s course. This one shows two specific goals for achieving the overarching goal of being more independent in a rehab facility. First is to use the call light to request assistance, and the other is to independently attend therapy sessions.

Paying attention to spouse and remembering tasks

Here’s a goal from the SCORE clinician guide (Chapter 4, Part I), with the wording adjusted for consistency. In this example, at baseline, the patient’s spouse reminds them of errands or chores at least twice before the patient does them (Level -1). The expected goal from therapy is to improve to only needing one reminder.

Goal: I will be able to pay attention to what my spouse tells me and remember more of what I’m told.

- +2: I repeat the information told to me in conversations immediately, independently (and complete the tasks).

- +1: I repeat the information told to me in conversations immediately with a minimal cue from my spouse (and complete the tasks).

- 0: My spouse reminds me 1 time of the information provided during conversations.

- -1: My spouse reminds me 2 or more times of the information provided during conversations.

- -2: My spouse reminds me of information from conversations daily and completes the tasks that I forget.

Remembering to take medication

Here’s another goal from the SCORE clinician guide (Chapter 4, Part I). At the start of therapy, this person can only take medications when their spouse reminds them two or more times per day. Their expected outcome from therapy is to only need one reminder per day.

Goal: I will remember to take my medication without cues from my spouse or family.

- +2: I remember my medication with my alarms and no reminders from my spouse.

- +1: I remember my medication with my alarms and my spouse reminds me less than 4 times a week.

- 0: My spouse reminds me 1 time per day to take my medications.

- -1: My spouse reminds me 2 or more times per day to take my medications.

- -2: My spouse gives me my medications each dose, each day.

Now that you’ve seen several examples, you may be ready to jump in and try it out. Continue on to read more specific details about how to write and use GAS goals.

How do we write goals using GAS?

Gather information

First, we start with finding out what our patient really wants to get out of therapy. We do this by asking open-ended questions and using the principles of Motivational Interviewing. During this process, we also gain insight into how motivated our patient is and what level of support they have from caregivers and family.

Then we do our assessment to determine current level of function, strengths and weaknesses, and response to trial therapy. Motivational interviewing and assessment aren’t mutually exclusive, but I like to get a sense of my patient’s goals before selecting assessment tools.

Based on this information and our clinical experience, we form an opinion about reasonable outcomes from therapy.

Collaborate with patient for GAS

Next, we could grab a piece of paper or a GAS worksheet and explain that we’re thinking about what could be different after a month of therapy (or however long). Jot a heading at the top, such as “Therapy outcomes” or “How therapy could improve my situation.” When I write things down for my patients, I usually ask them how they’d say it and use their words.

We could write the number scale down the left-hand side (+2, +1, 0, -1, -2). Or, if the negative numbers could be a distraction, we could use the wording instead. (Much better than expected, Better than expected, etc).

Then we could say, “Currently, you’re doing X. If that’s where you’re still at by the end of therapy, then that would be less than expected” and write it down at the -1 level (or -2 if it’s not possible to be worse). See if they agree that that is their current level.

Then ask our patient what they hope their performance is after a month of therapy. If you agree that it’s reasonable, write that down as Level 0.

If we think it’s too ambitious, as Don MacLennan modeled in the ASHA course, we can ask for permission to share our opinion. Then we can explain that based on our experience with people who were in similar situations that our patient is more likely to achieve X. And we could add their ambitious goal to the chart as a +1 or +2.

We could stop after having filled in the current level (-1 or -2) and the expected level (0). In order to use GAS for clinical work, we only have to be in agreement with our patient (or caregiver) regarding the current level of function and the expected outcome from therapy. This would provide us with our -1 (or -2) and 0 on the GAS outcome level chart.

But ideally, we would work with our patients to identify the better-than-expected scenarios (+1 and +2) and the remaining less-then-expected scenario (-1 or -2). The distance between levels should be equal.

Possible issues using GAS in clinical practice

This may seem like a lot to accomplish in an initial visit, and in most cases, I don’t think it’s necessary to do so. I find it helpful to take some time up front in therapy and really get at the heart of what my patient wants to accomplish. Focusing on a specific, meaningful, and motivating goal saves time in the long run and leads to better outcomes.

If our patient has much higher expectations, using GAS acknowledges the ambitious goal as a possible outcome, while identifying the more reasonable goal. Perhaps we could agree that our goal could be considered a short-term goal and the patient’s goal a longer-term goal (which may not be reached during therapy).

Another issue is that we may not be able to quantify a goal in a way that we can divide outcomes into five equal steps. If we’re doing research, it’s critical that the distance or difference between levels is equal because an equal distance between levels is necessary for the statistical analysis to be valid. But for clinical work, it doesn’t have to be perfect (according to Dr. Sohlberg in the TBI course).

But if we can’t divide the outcome into at least roughly equal steps, or our patient doesn’t want to use GAS, then we should simply write SMART goals.

Free tools for calculating the GAS score

SLPs aren’t known for loving math, so I’ll start out with the good news! There is a free app called GOALed, which is very easy to use. You can find it in the Apple store and Google Play. You can also download the free Excel GAS Calculation Sheet from King’s College London (follow the link and scroll down to the free resources).

Because the outcome levels are evenly spaced, it’s possible to identify a T-score for single goal. Better, we can combine all the goals to get a single T-score that reflects how successfully a person achieved their expected goals.

If determining the T-score for a single goal, the mean is 50 and the standard deviation (SD) is 10.

- +2 = 70 (+2 SD, outcome is much better than expected)

- +1 = 60 (+1 SD, outcome was better than expected)

- 0 = 50 (mean, the goal was achieved as expected)

- -1 = 40 (-1 SD, outcome was worse than expected)

- -2 = 30 (-2 SD, outcome is much worse than expected)

But there’s a complicated-looking formula to calculate the T-score for a set of goals. Hence the GOALed app or Excel worksheet!

I often have patients who improve with language or cognitive-communication therapy without the re-assessment data reflecting it. In those cases, it would be useful to calculate the T-score to demonstrate that therapy was indeed helpful. And since the GOALed app is so easy to use, my plan is to try it out and see how it goes.

Learn more about GAS

I highly recommend Don MacLennan and Dr. McKay Moore Sohlberg’s course in the ASHA Store: Beyond Workbooks: Functional Cognitive Rehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injuries. It’s currently free to ASHA Members through their complimentary ASHA Learning Pass, which expires 6/30/2020. (I have no financial interest).

King’s College London offers many great resources for GAS, including:

- An Excel Calculation Sheet.

- A Practical Guide.

- Training slides: GAS Made Easy

- GAS Light.

- A Record Sheet.

Cooper et al (2016) have made public all of the training and clinical materials used in their research with service members who underwent cognitive rehabilitation for mild concussion (the SCORE study mentioned in the examples above). Of particular interest to SLPs would be those listed under Chapter 4: Traditional Cognitive Rehabilitation for Persistent Symptoms Following Mild Traumatic Brain Injury, specifically:

- Clinician Guide to Individual Cognitive Rehabilitation Interventions.

- Client Manual for Individual Cognitive Rehabilitation Interventions.

Try Goal Attainment Scaling with a patient

Therapy has a much higher level of success if therapy focuses on goals that are meaningful and important to our patients. GAS gives us a concrete way to collaborate with our patients to identify goals and agree on what therapy is trying to achieve. An additional benefit is that GAS provides a statistically-valid outcome measure for how well our patient achieved their expected combined goals.

If you haven’t used GAS, why not give it a try? And if you’re using GAS, please share your tips!

Related Eat, Speak, & Think posts

- Collaborative goal-setting to identify meaningful cognitive goals.

- Assess readiness to change for better therapy outcomes.

- 5 ways I improved work-life balance as a home health SLP.

Free DIRECT download: GAS worksheet (patient handout). (Email subscribers get free access to all the resources in the Free Subscription Library.)

Lisa earned her M.A. in Speech-Language Pathology from the University of Maryland, College Park and her M.A. in Linguistics from the University of California, San Diego.

She participated in research studies with the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) and the University of Maryland in the areas of aphasia, Parkinson’s Disease, epilepsy, and fluency disorders.

Lisa has been working as a medical speech-language pathologist since 2008. She has a strong passion for evidence-based assessment and therapy, having earned five ASHA Awards for Professional Participation in Continuing Education.

She launched EatSpeakThink.com in June 2018 to help other clinicians be more successful working in home health, as well as to provide strategies and resources to people living with problems eating, speaking, or thinking.

Be First to Comment