You may be surprised to learn that there are a number of problems with SMART goals! Learn how Goal Attainment Scaling makes SMART goals better. You’ll see the common GAS format, the staircase visual analogy, and 3-milestone GAS. I also share links to free training materials and resources so you can start using GAS today.

Free DIRECT download: Logan (2023)’s GAS template (cheat sheet/patient handout). (Email subscribers get free access to all the resources in the Free Subscription Library.) (Logan (2023), “A practical guide to administering Goal Attainment Scaling.” General Resource, Goal Attainment Scaling – blank template, https://www.afn.org.au/for-researchers/gas, Accessed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivs 4.0 International License, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en)

Outline:

- The problem with SMART goals.

- GAS goals are very specific and personal.

- What is Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS)?

- The staircase analogy may be more motivating.

- 3-milestone GAS.

- Free materials for learning and using GAS.

- Related Eat, Speak, & Think posts.

- References.

The problem with SMART goals

Do you think that writing SMART goals in adult rehabilitation is strongly supported by research? I was surprised to learn that it’s not.

So what are some of the potential problems with using SMART goals? The SMART goal format is not well-defined, SMART goals may not reflect patient wishes, and systematic reviews haven’t found strong evidence that goal-setting improves clinical outcomes. Even the act of goal-writing may not improve clinical outcomes! (Bard et al, 2023; Dekker et al, 2019; Nobriga & St. Clair, 2018; Wade 2009)

The concept of SMART goals is ill-defined

The elements of a SMART (or SMARTER) goal are not well defined online or in research. Wade (2009) has a table listing many different meanings attached to each letter in the acronym. For instance, the “S” can stand for:

- Specific

- Significant

- Stretching

- Simple

- Stimulating

- Succinct

- Straight-forward

- Self-owned

- Self-managed

- Self-controlled

- Strategic

- Sensible.

Even if we all agree that “S” stands for “specific”, it is still interpreted differently in the research literature (Bard-Pondarré et al., 2023). They write that “specific” has at least 3 possible interpretations:

- Explicitly-defined behaviors that are indicative of attainment of the client’s general goal.

- Directly relevant to a particular person and their unique needs.

- Relevant to the research study the person is participating in.

You may be as surprised as I was to learn that even the notion of goal writing has been called into question.

Systematic reviews of studies that involved adults participating in rehabilitation found only limited, rather low-quality evidence that goal-setting indeed improves clinical outcomes.

Dekker et al., 2019, p. 4

SMART goals may not reflect patient wishes

“Nevertheless, goal-setting in rehabilitation is controversial. One of the major areas of controversy concerns how to set goals that clients find personally meaningful.

Dekker et al., 2019, p. 4

Dekker et al. goes on to say that clients tend to set goals that are broad, hopeful, and aspirational. Clinicians often find these goals unrealistic and set short-term SMART goals which may or may not relate to the client’s goals in a meaningful way. Patients may find the goal-setting process “prescriptive and inflexible” and not relevant to their own goals.

Can you see the patient in these SMART goals?

We all know that our goal is to provide person-centered care. I’d bet we all believe we’re doing this. After all, we interview and assess our patients, and then we set goals based on what we find. That’s person-centered, right? Well, not necessarily.

Establishing the patient’s goals is not trivial, and it is rarely wise to make assumptions about the wishes and expectations of individual patients in any situation, however obvious they may appear.

Wade, 2009, p. 293

Let me give you an example. Here are three memory goals from Adult Speech Therapy’s goal bank that I think are representative of the kinds of goals we write. These goals are SMART or will be once the treating SLP adds in the missing elements.

- The patient will recall sentence-level information after a 30-minute delay using the spaced retrieval technique.

- The patient will recall 5 or more items (i.e. grocery list, medication list, etc.) after a 30-minute delay given intermittent minimal verbal cues in order to increase independence during functional memory tasks.

- The patient will recall page-level information and answer questions about the material at 80% accuracy given visual cues after a 30-minute delay in order to increase independence.

As you read these goals, can you get a clear picture in your mind about the real-life problem that prompted them? I can’t. (This is not a criticism of the goal bank!)

Does Patient #1 need to remember to use their walker? Do they need to remember where they put their glasses or their keys? Maybe they need to remember that their wife will visit them in the SNF during lunch so they reduce repetitive questions? Or perhaps it’s a problem with prospective memory. Does the patient need to remember what they walked into the kitchen for?

The same goes for Patients #2 and #3. Why were these tasks selected? Are they targeting specific real-world needs, or are they a way to improve “functional memory”. Will the patient see a definite improvement in their life after therapy, or is the hope that improving performance on memory tasks will translate to real-world gains?

Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) does not solve all of these problems, but GAS is an excellent tool for helping us to write and target personalized, meaningful goals in therapy.

GAS goals are very specific and personal

Working with our patient to write their goals in GAS form can result in much more specific and personalized goals than traditional SMART goals. GAS also allows the patient to see their more hopeful goals acknowledged as “stretch” goals.

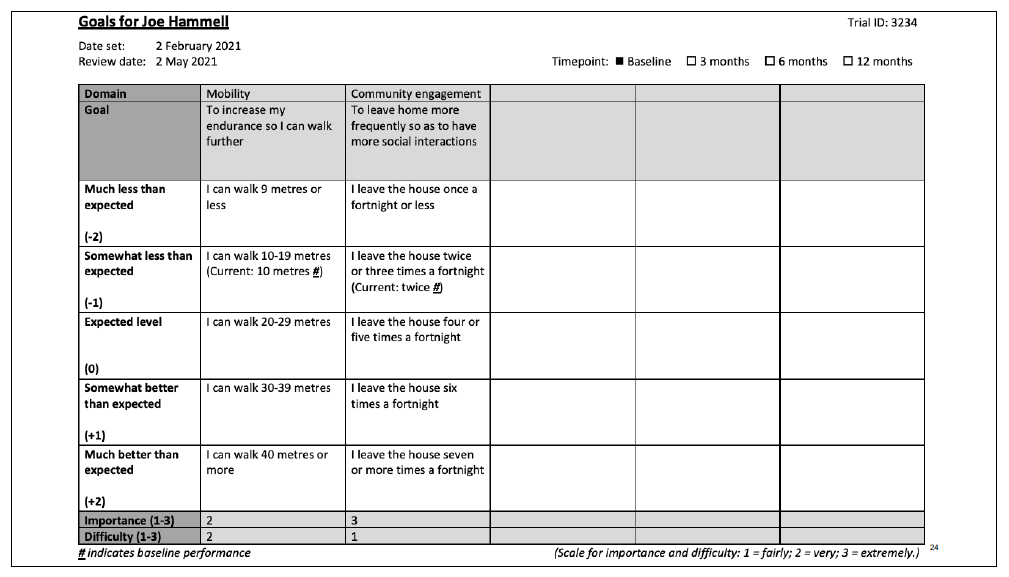

Take a look at these two physical therapy goals written out using GAS methods. This person has two SMART goals, one for walking longer distances and one for leaving home more often to improve social connection. The clinician then worked with the patient to define what success looks like to them. Their baseline is written at the (-1) level and their expected outcome is written at the (0) level.

When you read through the GAS goals, do you get a pretty good idea of this patient’s current functioning and their goals? I do!

What is Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS)?

Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) is a way of developing personal outcome measures. GAS can be used as a subjective, interview-based, patient-referenced outcome measure (PROM) or as a personalized, performance-based objective measure.

If you use GAS as a PROM, it is still recommended that you make the outcome measurable by the patient. In other words, GAS goals should still have the recommended SMART elements. (Bard-Pondarré, et al., 2023; Krasny-Pacini et al., 2013; Logan et al., 2024)

GAS is typically defined on a 5-point scale ranging from -2 to +2, which you can see in the example above.

- +2: much better than expected

- +1: better than expected

- 0: expected outcome of therapy

- -1: worse than expected

- -2: much worse than expected

For clinical practice, 0 level is often simply the patient’s “goal”, assuming all possible means will be employed to achieve it, within a given time-frame that may be extended without being a threat to GAS validity.

Bard-Pondarré et al., 2023, p. 7

Where to write the pre-treatment baseline

Logan et al. (2024) recommends that (-1) be assigned the patient’s pre-treatment baseline (current level of performance), unless there is no conceivable worse performance, in which case the CLOF would be assigned to (-2). An example of this is when a patient’s goal is to re-gain use of a calendar, and they’re not using it at all prior to therapy. If a patient has a progressive disorder and their goal is to maintain their CLOF, then their pre-treatment baseline would be assigned to (0).

In a slight difference, Krasny-Pacini et al. (2013) report that the patient’s pre-treatment baseline is commonly set at (-2).

So you may choose where to list the patient’s pre-treatment baseline (CLOF):

- (-1) allows for a score should the patient decline.

- (-2) allows for a score should the patient improve but not meet their goal, which is level (0).

- (0) allows for a successful outcome for maintaining the pre-treatment baseline (progressive disorder).

Tips for writing a GAS chart

Bard-Pondarré, et al. (2023) and Logan (2023) suggest:

- Only change one element between steps (ex. frequency OR level of independence, but not both). Write one chart for each element that may change as a result of therapy.

- Make the steps equidistant, to measure an equal amount of change.

- Use a range for continuous measures.

- Write the goal in plain language.

- For the pre-treatment baseline, use what the patients generally do, not what they do on their worst or best day.

- Negotiate with the patient to agree on an expected outcome, placing more hopeful goals at (+1) and (+2) as stretch goals.

- Provide emotional support for patients who have a fear of failure.

Mistakes to avoid in GAS

Bard-Pondarré, et al. (2023) and Logan (2023) report some common pitfalls to avoid:

- Measuring change in more than one way on a single chart.

- The distance between possible outcome levels is not equal.

- Incorrect assessment of pre-treatment baseline.

- Levels that are too easy to achieve or aren’t meaningful.

- Writing levels that are too optimistic or have too long a time-frame.

- Not specifying a time-frame.

The staircase analogy may be more motivating

The traditional GAS format has been criticized for being depressing. After all, who wants to work towards a “0” outcome? Bard-Pondarré, et al. (2023) suggest a 5-level staircase visual analogy, with the bottom step being the starting point and the goal being the middle step (developed by Bard-Pondarré & Castan, 2017).

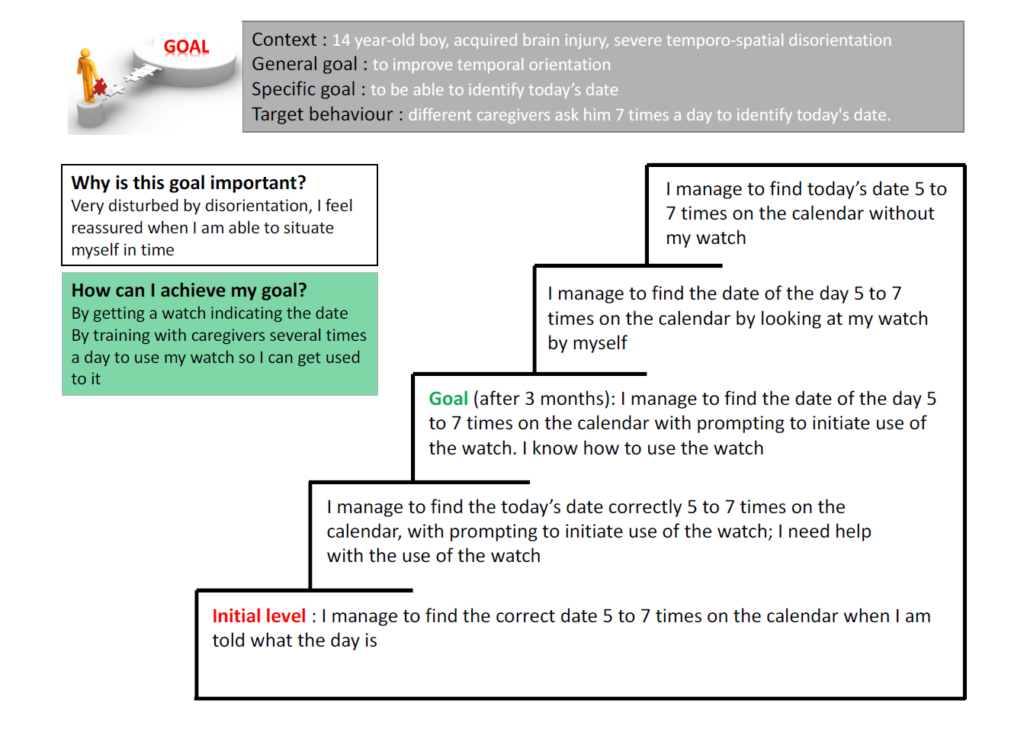

Here’s an example of GAS from Bard-Pondarré, et al. (2023) written for a 14-year old boy with an acquired brain injury who is disturbed by not knowing what day it is on a calendar.

The staircase visual tool may be more intuitive for patients to understand than the (-2) to (+2) chart. In the above example, the CLOF is set on the bottom step, which corresponds with (-2). As discussed above, a specific patient’s CLOF may be set on the 2nd step up (-1), or on the middle step (0).

3-milestone GAS

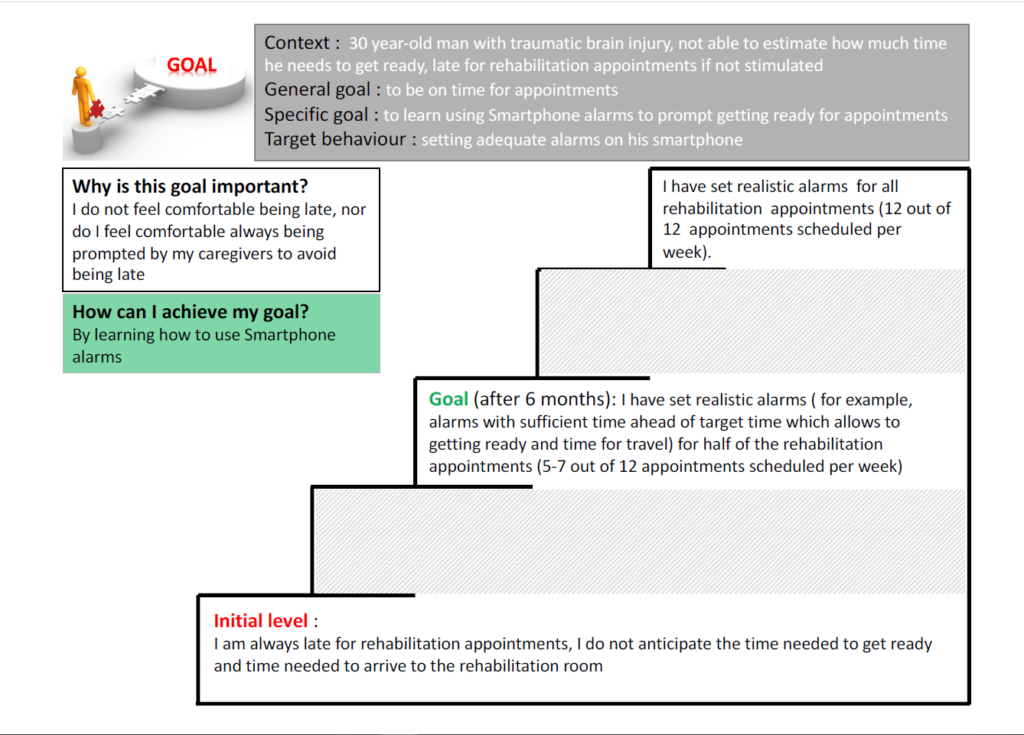

Writing out all 5 steps can be time-consuming and doesn’t allow for any flexibility for scoring outcomes when a patient improves in unexpected ways. Krasny-Pacini et al. (2013) report that writing GAS with only 3 of the 5 levels specified prior to therapy is an appropriate option for clinical practice.

The levels we would describe are (-2) much worse than expected, (0) expected outcome, and (+2) much better than expected. This saves time in specifying the levels, plus it allows for scoring should the patient end up between milestones in an unexpected way.

Here is an example using the staircase analogy:

Free materials for learning and using GAS

For an easy-to-read, comprehensive overview of GAS plus a detailed framework for how to use it in clinical practice, read Bard-Pondarré, et al. (2023). The supplementary material includes worked examples and templates.

If you’d like an in-depth learning experience, complete with PowerPoint slides, videos, and a handbook, check out Logan (2023) and Logan et al. (2024).

Related Eat, Speak, & Think posts

- Goal Attainment Scaling tutorial.

- Assess readiness to change for better therapy outcomes.

- Collaborative goal-setting to identify meaningful cognitive goals.

- Write better cognitive goals with 54 daily activities.

References

- Adult Speech Therapy. (2023, November 9). Goal Bank for Adult Speech Therapy (150 SLP Goals!). Retrieved March 9, 2024 from https://theadultspeechtherapyworkbook.com/goal-bank-for-adult-speech-therapy-150-slp-goals/

- Bard-Pondarré, R., Villepinte, C., Roumenoff, F., Lebrault, H., Bonnyaud, C., Pradeau, C., Bensmail, D., Isner-Horobeti, M.-E., & Krasny-Pacini, A. (2023). Goal Attainment Scaling in rehabilitation: An educational review providing a comprehensive didactical tool box for implementing Goal Attainment Scaling. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 55, jrm6498. https://doi.org/10.2340/jrm.v55.6498

- Dekker, J., de Groot, V., ter Steeg, A. M., Vloothuis, J., Holla, J., Collette, E., Satink, T., Post, L., Doodeman, S., & Littooij, E. (2019). Setting meaningful goals in rehabilitation: rationale and practical tool. Clinical Rehabilitation, 34(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215519876299

- Krasny-Pacini, A., Hiebel, J., Pauly, F., Godon, S., & Chevignard, M. (2013). Goal Attainment Scaling in rehabilitation: A literature-based update. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 56(3), 212–230. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2013.02.002

- Logan, B. A practical guide to administering Goal Attainment Scaling. Brisbane: University of Queensland: Centre for Health Services Research – Australian Frailty Network, 2023. https://www.afn.org.au/for-researchers/gas/

- Logan, B., Viecelli, A. K., Pascoe, E. M., Pimm, B., Hickey, L. E., Johnson, D. W., & Hubbard, R. E. (2024). Training healthcare professionals to administer Goal Attainment Scaling as an outcome measure. Journal of patient-reported outcomes, 8(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-024-00704-0

- Nobriga, C., & St. Clair, J. (2018). Training Goal Writing: A Practical and Systematic Approach. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 3(11), 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1044/persp3.SIG11.36

- Wade, D. T. (2009). Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23(4), 291–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215509103551

Free DIRECT download: Logan (2023)’s GAS template (cheat sheet/patient handout). (Email subscribers get free access to all the resources in the Free Subscription Library.) (Logan (2023), “A practical guide to administering Goal Attainment Scaling.” General Resource, Goal Attainment Scaling – blank template, https://www.afn.org.au/for-researchers/gas, Accessed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivs 4.0 International License, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en)

Featured image is from Bard-Pondarré et al. (2023), “Goal Attainment Scaling in rehabilitation: An educational review providing a comprehensive didactical tool box for implementing Goal Attainment Scaling.”, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10301855/, Accessed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/)

Lisa earned her M.A. in Speech-Language Pathology from the University of Maryland, College Park and her M.A. in Linguistics from the University of California, San Diego.

She participated in research studies with the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) and the University of Maryland in the areas of aphasia, Parkinson’s Disease, epilepsy, and fluency disorders.

Lisa has been working as a medical speech-language pathologist since 2008. She has a strong passion for evidence-based assessment and therapy, having earned five ASHA Awards for Professional Participation in Continuing Education.

She launched EatSpeakThink.com in June 2018 to help other clinicians be more successful working in home health, as well as to provide strategies and resources to people living with problems eating, speaking, or thinking.

Be First to Comment