I recently worked with two patients with severe acquired apraxia of speech (AOS) just as I was really beginning to understand the difference between activity and participation goals. I used my usual therapy approach with Archie, but I focused on participation with Patrick. While both patients had similar reductions in their AOS, only Patrick felt like he had improved. As a participation approach narrows the scope of the goal and changes how success is defined, I believe it supports the rebuilding of confidence. I’m sharing these two case studies in case you find it helpful. (Just as an aside, I *thought* I had been doing participation-focused therapy all along; turns out I was wrong.)

Free DIRECT download: 5 types of ST goals based on ICF (cheat sheet). (Email subscribers get free access to all the resources in the Free Subscription Library.)

Outline:

- Sample AOS goals for different ICF levels.

- Understanding participation-focused intervention.

- Meet my patients: Archie and Patrick.

- The core AOS therapy was the same.

- How therapy was different.

- Archie’s outcomes.

- Patrick’s outcomes.

- Better AOS outcomes with a focus on participation.

- Learn more about participation goals.

- Related Eat, Speak, & Think posts.

- References.

Sample AOS goals for different ICF levels

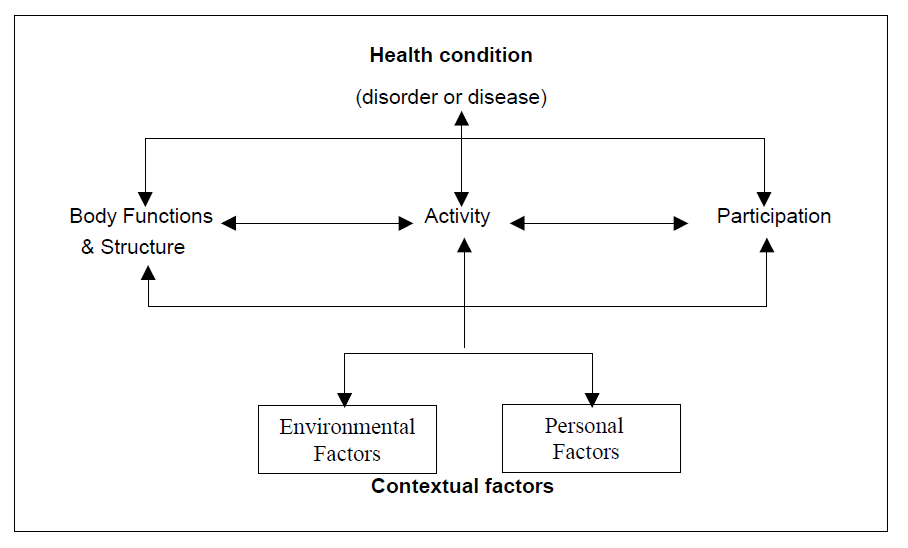

Check out the WHO ICF below (ICF, WHO 2002, p. 9). As SLPs, we have 5 potential targets for therapy: body functions and structure, activity, participation, environmental factors, and personal factors.

When applying the ICF to acquired Apraxia of Speech (AOS), we could write the following sorts of goals:

- Function/Structure: Patient will produce consonant clusters in two-syllable words with 80% accuracy independently within 4 weeks.

- Activity: Patient will produce at least 8 of 10 personally-relevant words accurately independently within 4 weeks.

- Participation: Patient will successfully schedule a salon appointment using any recommended support independently within 4 weeks.

- Physical and Social Environmental Factors: Patient will advocate for herself by identifying as a stroke survivor and asking for additional time to speak when on the phone with medical professionals within 4 weeks.

- Personal Factors: Patient will report that his confidence in speaking with extended family has improved from 1/10 to 5/10 on a scale where 1 = not confident at all and 10 = very confident within 4 weeks.

ASHA has a helpful infographic showing how to apply the ICF to acquired apraxia of speech (link is “Person-Centered Focus on Function: Acquired Apraxia of Speech”, under “Treatment” section).

Understanding participation-focused intervention

I’ve been doing a lot of reading on the subject of goal-writing, and I was quite honestly taken aback when I learned that the following goal is not a participation-level goal:

Not a participation-level goal:

Client will demonstrate speech intelligibility of 90% or higher at the end of 8 weeks to facilitate participation in knitting club.

Baylor & Darling-White, 2020, p. 1341

This is exactly the type of goal I’d been writing, believing it was participation-focused. In my mind, if my patient improves their speech intelligibility, then of course they will improve their participation in knitting club.

What Baylor & Darling-White (and other researchers) have done is convinced me that the goal above targets activity, not participation. Research doesn’t support a strong correlation between improvement in function/activity with improvement in participation.

Why?

Well, for one thing, the above goal doesn’t take physical environment, social environment, or personal factors into account. Those are all very powerful influences that can either help or hinder a patient from resuming life participation activities.

I recommend reading Baylor & Darling-White’s paper to better understand participation-level goals. In a nutshell, they recommend that we select one meaningful real life communication-based transaction to focus on. That is the participation-level goal. Then we can write any number of other goals to address the other levels of the ICF, but the trick is to orient them all towards that participation-level goal. Understanding their proposed framework really helped me improve how I approach my patients.

Meet my patients: Archie and Patrick

I recently worked with two patients with severe apraxia of speech, but there was one key difference in my treatment plans. For Archie, the first patient, I wrote what I thought was a participation-level goal. Turns out, it was really an activity-level goal. Shortly after I learned the difference, I met Patrick and made sure that I wrote a participation-level goal for him.

Archie and Patrick both had severe apraxia of speech (AOS), as well as aphasia. For each of them, the AOS was the larger limiting factor, so therapy focused on motor speech.

From a speech therapy perspective, both patients had very good outcomes.

But from a life participation standpoint, one patient had significantly better outcomes. I bet you can guess which one that was!

Focusing speech therapy on life participation is different from the medical model many of us are used to. If you’re interested in learning more about the biopsychosocial model recommended by the WHO, CMS, and ASHA, you may find these case examples helpful!

Archie – focus on improving speech production

A is for activity, so I named this patient Archie. Archie was a 78-year-old married individual living in the community. Prior to his stroke, he was very involved with his family and well-known in his neighborhood. Archie suffered a stroke which primarily affected speech and language. He didn’t need an assistive device, and swallowing wasn’t affected.

Since communication was the only impairment, Archie didn’t qualify for in-patient rehab, so I met him quite soon after his stroke. Archie had global aphasia and severe apraxia of speech. He was able to speak at the phrase/short sentence level, at times able to take several conversational turns. At other times, he was barely able to say a word. At no point was he able to communicate normally. This was very frustrating for Archie, but he was motivated to do whatever he could to recover his speech.

Archie’s primary goal was to talk normally. This is a huge goal, even from an activity standpoint, so I always try to find personally-relevant words. We came up with a list of 10 words/phrases, including the names of his kids. (I tried multiple times to introduce AAC, but Archie was not interested.)

Here’s the goal that I wrote:

- Archie will demonstrate the ability to produce 8/10 words or phrases on his personalized word list using any recommended strategy independently to improve his communication for functional daily tasks within 6 weeks.

Why Archie’s goal is not a participation goal

When I wrote this goal, I thought it was a participation-level goal because we were targeting words that he would use in daily conversation. I would help him regain the ability to say these important words and phrases, and then he would carry it over into general conversation. Hence, our therapy would improve his life participation.

The only problem is, this is not a participation-level goal.

How can we tell?

Because Archie could conceivably meet this goal by the end of therapy without improving his ability to use those words in actual conversation.

In meeting this goal, speech therapy would focus on improving body function and activity. In other words, improving how Archie moved his articulators to produce personally-relevant words.

Speech therapy did not address the physical environment, social environment, or personal factors. I never observed a conversation between Archie and his wife or son, although they were always in the house during my sessions. Archie’s wife was very talkative and when she checked in at the start and end of each session, she dominated the conversation. She never stayed for the session, even though I frequently invited her to.

Our shared understanding was that I was there to help Archie talk better. His family didn’t think they were relevant to the process. If they had joined in, my focus would have been on how they could support and cue Archie.

In summary, an easy way to tell if your goal is activity or participation is to ask yourself, is it at all possible for my patient to meet this goal without improving anything in their day-to-day life? If your answer is “yes”, then you’re looking at an skill or activity goal.

It’s fine to write skill- and activity-level goals! But if we want to provide participation-level intervention, we should have at least one participation-level goal. Curious to see what an AOS participation-level goal might look like?

Patrick – focus on improving life participation

I’ll call this patient Patrick, as this is my “participation-focused” patient. Patrick is an 81-year-old widow, living alone in the community. Prior to his stroke, he was fully independent. Patrick has many friends in the area, and often met them at a coffee shop for a long visit to start the day.

Patrick had a stroke three months before I met him. He was hospitalized and then received three weeks of inpatient rehab. I assessed Patrick for home health services nearly five weeks after the CVA. While he presented with aphasia, apraxia of speech, and dysphagia, I’m going to focus on AOS as that was the most salient barrier to Patrick resuming normal communication activities.

Specifically, when I met him, Patrick refused to talk to most of his friends and family. He refused to talk on the phone with anyone other than his daughter. He refused visits from his friends and most of his family when they asked to come.

Since I’d updated my understanding of participation-level goals by the time I met Patrick, I took the time in my initial assessment to pinpoint a specific communication-related situation that Patrick wanted to improve.

Naturally, Patrick wanted to “talk normally”. We narrowed that down to “talking on the phone”. And then we narrowed that down again to making medical appointments. Prior to the CVA, Patrick managed his own schedule. Now his daughter was making all of his appointments, and he wanted to regain that independence.

Writing a participation-focused AOS goal

Now that I knew Patrick’s primary participation goal, I collected a baseline measure so we could see if the therapy helped him. I grabbed a piece of paper and a pen and drew a number line, from 1 to 10. Together, we came up with this title: “How comfortable I feel making an appointment with my primary care doctor.”

Then I asked him what the endpoints should mean. We figured out that 1 = “not at all” and 10 = “very”. Then he rated himself as a “1”. Then I asked him what level he thought he could be at in 6 weeks, since that is when I believed we would be discharging. He selected “7”.

Here is the goal I wrote, using the self-anchored rating scale as a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM):

The goal I wrote:

Patrick will report improved confidence in calling his PCP to make an appointment by rating himself at least a “7” on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 = not at all and 10 = very (baseline = 1/10) within 6 weeks.

Now we can ask ourselves the activity vs participation question: Is it possible for Patrick to meet this goal without improving anything in his day-to-day life?

I think the answer is “no”! If he is reporting that his confidence has improved, then that’s a meaningful outcome.

But if you’re worried that your patient will inflate their score at the end of therapy, you could write the goal in a different way.

A different participation-focused goal:

Patrick will successfully call his PCP to make or confirm an appointment independently within 6 weeks.

We could still use the self-anchored rating scale as a PROM, but Patrick would actually have to make an appointment with his PCP to meet this goal.

The core AOS therapy was the same

I used articulatory kinematic techniques with both Archie and Patrick, as this approach has the best evidence according to the systematic reviews described by Wambaugh in her MedBridge course (n.d., slide 38). If you’re an SLP, you’re probably familiar with these common techniques (slide 46):

- Repeated practice

- Modeling.

- Integral stimulation.

- Articulatory placement cues

- Shaping.

- Verbal feedback.

- Minimal contrast practice.

In addition to the above approaches, I used scripting with both patients. I tried to teach both patients self-cueing strategies. Finally, I followed the principles of motor learning, switching between blocked and distributed practice, varying the context, paying attention to feedback type/frequency/timing, etc.

How therapy was different

As my “activity” patient, Archie had a list of 10 words/phrases that we focused on in therapy. I started with a probe to see how many he could say independently when given a description. Then I used the AOS strategies above to focus on improving his ability to say these words in isolation and then dynamically increased to phrases and sentences as he was able.

I taught Archie to self-cue looking at mouth-shape photos, reading, and writing. I tried multiple times to have his wife join us in therapy. She always “checked-in” at the start and end, but never stayed for the session. I taught her strategies she could use to support communication, but she always declined to try them out in the session or watch me use them.

Patrick, as my “participation” patient, focused on the predictable conversation of calling a doctor to make an appointment. We still used the same AOS therapy strategies, and I still taught him how to self-cue, but every session was focused on having a specific conversation.

I absolutely intended to have Patrick call his PCP during each session (with me providing as much cueing as he needed for each conversational turn). At first, he was resistant to the idea. And then after a couple of weeks, it was like a switch flipped. Patrick was no longer concerned about his ability to call his PCP. His confidence level was high, and he had met that goal. So we picked other conversational words to focus on in therapy until he went on to out-patient therapy.

I think the key differences between Archie and Patrick were the scope of the goal and how success was measured. I believe this helped Patrick gain confidence faster compared to Archie, although I don’t have evidence to support that idea.

- Scope of the goal:

- Archie was focused on using 10 words/phrases anytime they came up in conversation.

- Patrick was focused on making a specific type of phone call.

- Success was characterized differently:

- Archie was focused on accurate production.

- Patrick was focused on successfully making or confirming an appointment.

Archie’s outcomes

Archie’s apraxia of speech improved to the mild-moderate range, and he was talking more fluently in conversation. He was able to say 9/10 words/phrases on his word list, independently self-cueing as needed, during the session. Using those words outside of the session was hit or miss, as we may expect from AOS. While he was self-cueing in the sessions, he wasn’t self-cueing in conversations with family.

His wife reported that he was having some good conversations with family and friends who came to the house, but he refused to talk on the phone or leave the house unless absolutely necessary. He didn’t feel confident at all that he could communicate in public.

So, even though Archie objectively showed significant progress with speech therapy, he didn’t feel like he had improved.

I think focusing on practicing his word list in therapy created an expectation that success was an accurate production. And since he couldn’t easily and fluently say those words/phrases 100% of the time, he felt like he hadn’t progressed.

If I could go back in time, I would pick a specific conversation to work on. In the spirit of participation, I would have a frank discussion with his wife and son about participating in the sessions. And instead of drilling the personalized word list, I would focus on the target conversation and teaching strategies to support successful communication rather than aiming towards accurate production.

Patrick’s outcomes

Like Archie, Patrick’s AOS improved to the mild-moderate range. Also like Archie, Patrick was now accepting visitors and was able to carry on conversations, even though he wasn’t back to “normal.”

Unlike Archie, Patrick’s confidence had surged over the course of therapy. By the time of discharge, he was answering the phone and making phone calls to family and friends. He did call his PCP to make an appointment the week I discharged him. He was looking forward to getting back into the community.

Better AOS outcomes with a focus on participation

I know we can’t really compare Archie and Patrick. They are two distinct people with a lot of factors that they didn’t have in common.

Having said that, I found it really striking to be working with two similar patients just before and just after learning about participation-level goals. Patients who objectively made significant gains in motor speech skills and real-world conversation, but patients who had such different perceptions about the outcome of therapy.

I don’t know that Archie’s feelings about his progress with speech therapy would have been any different had I focused on participation rather than activity. But I think it could have.

It’s easy for me as a speech-language pathologist to see the link between teaching someone how to say important words better and seeing them generalize that to their daily life. It feels so obvious to me. My role as an SLP is to teach my patient how to talk better, and my patient’s job is to apply that to their daily life.

But that’s the old, medical model way of doing speech therapy. CMS and the WHO now expect us to provide intervention at the participation level. We’re expected to follow a biopsychosocial model. Put simply, this means that it’s our job to do everything we can to support our patients applying what we teach them to real life situations.

I could have done this with Archie by selecting a single conversation to focus on, then looking at barriers and opportunities and going on from there.

Learn more about participation goals

If you’re in doubt about whether you’ve written an activity-focused goal or a participation-focused goal, ask yourself if your patient could conceivably meet your goal without improving their day-to-day participation. If your answer is “yes”, then you’ve written an activity-focused goal.

Baylor & Darling-White’s paper – I highly recommend it. It was instrumental in helping me understand the opportunities I’ve been missing with some of my patients.

Nobriga & St. Clair (2018) have an excellent goal writing tutorial with a handy flow chart (updated).

I distilled many, many hours of reading and learning into a 2-hour CE course through MSCC (not an affiliate link). While the title of my recorded presentation is “What Really Happens When Patients Go Home”, a large part of the talk is focused on writing meaningful, participation-focused goals for any setting. I shared what I learned from many sources, including the paper above.

Related Eat, Speak, & Think posts

- Tips for dynamic speech assessment.

- A PROMising shift: SLPs offer person-centered care.

- An easy way to write participation-level speech therapy goals.

References

- Baylor, C., & Darling-White, M. (2020). Achieving Participation-Focused Intervention Through Shared Decision Making: Proposal of an Age- and Disorder-Generic Framework. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(3), 1335–1360. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-19-00043

- Nobriga, C., & St. Clair, J. (2018). Training Goal Writing: A Practical and Systematic Approach. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 3(11), 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1044/persp3.SIG11.36

- Wambaugh, L. (n.d.) Treatment of Acquired Apraxia of Speech: Therapeutic Approaches and Practice Guidelines. Retrieved April 27, 2024 from https://www.medbridge.com/course-catalog/details/treatment-of-acquired-apraxia-of-speech-therapeutic-approaches-and-practice-guidelines/

Free DIRECT download: 5 types of ST goals based on ICF (cheat sheet). (Email subscribers get free access to all the resources in the Free Subscription Library.)

Featured image by Reem Mansour from Pexels, on Canva.com.

Lisa earned her M.A. in Speech-Language Pathology from the University of Maryland, College Park and her M.A. in Linguistics from the University of California, San Diego.

She participated in research studies with the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) and the University of Maryland in the areas of aphasia, Parkinson’s Disease, epilepsy, and fluency disorders.

Lisa has been working as a medical speech-language pathologist since 2008. She has a strong passion for evidence-based assessment and therapy, having earned five ASHA Awards for Professional Participation in Continuing Education.

She launched EatSpeakThink.com in June 2018 to help other clinicians be more successful working in home health, as well as to provide strategies and resources to people living with problems eating, speaking, or thinking.

Be First to Comment